University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Engineering Shifts to English-Language Instruction

Starting this academic year, the University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Engineering has adopted English as the principal language of instruction. The move aims to create a globally competitive educational environment, aligning with top institutions worldwide. However, faculty members are also expected to adapt by learning new teaching methods. Similar initiatives are gradually spreading across other leading Japanese universities.

“I’ve always believed that switching to English was necessary. Students become more comfortable in an English-speaking environment, and it opens up more opportunities for them to go abroad,” said Professor Yasuhiro Kato, Dean of the Graduate School of Engineering and Faculty of Engineering, passionately explaining the rationale behind the shift.

Kato’s first overseas research experience was at Harvard University in the 1990s, when he was 37. Although he had written his undergraduate and doctoral theses in English, he struggled with everyday conversations. “I don’t want our students to go through the same experience,” he said. Upon assuming the role of dean in April 2023, Mr. Kato began seriously considering the transition. In fact, the idea of English-taught courses had been discussed for over a decade.

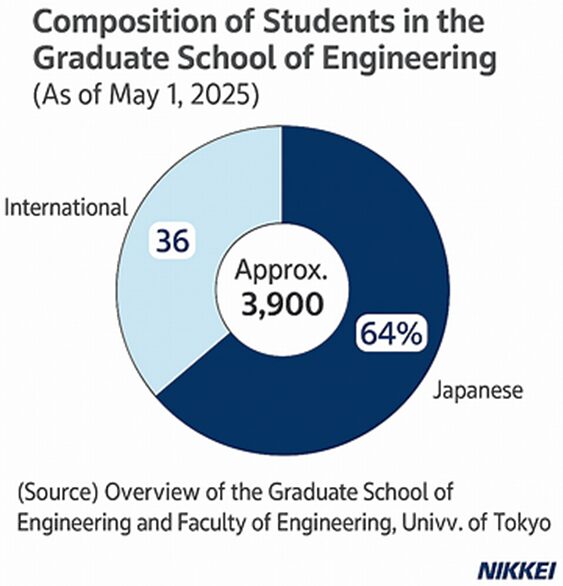

Currently, about one-third of the approximately 3,900 students enrolled in the master’s and doctoral programs are international students. The shift to English is also seen as a way to diversify the student body, which has been heavily skewed toward students from Asia. The university’s decision also reflects its ambition to be designated as a “University for International Research Excellence,” a status supported by a ¥10 trillion government fund. At present, over 70% of courses are taught in English, with a target of raising that figure to 90%. Some flexibility remains for subjects like Japanese architecture or lectures by external instructors, which may still be conducted in Japanese.

According to Associate Dean Kohei Tsumoto, the shift to English is also driven by the accelerating pace of knowledge creation. “Cutting-edge research is published and circulated in English. The flow of information is speeding up, and new terminology is constantly emerging,” he explained. “There’s no time for translation. Even conversations among Japanese colleagues naturally shift to English. The need to use English as a tool is growing stronger. Sometimes I think language might be one of the main reasons people fall behind.” Mr. Tsumoto also pointed to the rising English proficiency at top universities in neighboring countries. Seoul National University, with which UTokyo exchanges courses, has made significant strides in English education. “They’ve had serious discussions and are pushing forward. Tsinghua University in China is doing the same. We should accelerate our efforts as well,” he said.

Japan’s Top Universities Must Evolve

From a global perspective, Japan’s leading universities can no longer afford to maintain the status quo. Graduate schools are the main stage for international competition and collaboration. While preserving native-language education is important, institutions like the University of Tokyo must create learning environments that reflect their global standing. That means embracing English-language instruction.

The Challenge of Teaching in English

Switching to English is not easy—especially in STEM fields, where many students struggle with the language. Experts warn that elite universities often underestimate the difficulty. Teaching in English requires more than fluency; it demands a shift in teaching style and mindset.

Diversity Demands New Skills

As international student diversity grows, faculty must develop intercultural communication skills. True reform requires thoughtful preparation, not just policy changes.

Sophia University’s Bold Initiative

Sophia University is preparing to launch a new Department of Digital Green Technology in April 2027. Half of the 50 incoming students will be international, and all classes—including exams and assignments—will be conducted in English. Eight of the ten faculty members will be newly hired.

Vice President Makoto Ikeda, an expert in English education, stresses the need for structured faculty training. “The English used in research is different from the English used in teaching,” he explains. “Each academic field has its own language nuances, so training must reflect those differences.”

Dean Tomonori Shibuya adds, “To solve global challenges, the ability to negotiate in English is essential. We want to develop faculty training based on solid research and practice.”

Faculty Development at UTokyo

The University of Tokyo’s Graduate School of Engineering has hosted two workshops led by UK experts on effective English-language teaching. More training is planned, along with surveys of faculty and students to guide improvements.

Faculty development (FD) programs are rare at research-focused universities in Japan. But when major reforms are underway, learning how to teach becomes essential. Even traditional institutions like UTokyo must now face this challenge. Listening humbly to student feedback is part of the process.

Waseda’s New Curriculum

Waseda University recently announced a new curriculum for its School of Political Science and Economics starting in 2027. Japanese students will be required to take new English-taught courses alongside international peers. These “co-learning” environments are gradually expanding across campuses.

Two Key Benefits of English-Language Reform

- Internal Internationalization Creating global experiences within Japan is more important than ever. After a post-pandemic surge in outbound study, Japanese students now face challenges like global instability and a weak yen. Changing students’ inward-looking mindset will take time, but internationalizing domestic education is a powerful step forward.

- Stimulating High School English Education High school students’ English proficiency is improving. According to a government survey, 27% of general-track students reached CEFR B1 level or higher in 2024. The national goal is 30% by 2027—a target within reach.

A Turning Point for Japanese Higher Education

As UTokyo’s Associate Dean Kohei Tsumoto puts it, “True internationalization is beginning.” The Japan Association of National Universities has set a long-term goal: 30% of students should be international. The momentum is building—and Japan’s universities must rise to meet it.

Source: Nikkei. (2025, September 22). University of Tokyo’s Graduate Engineering Program Goes English to Boost Globalization

https://www.nikkei.com/article/DGXZQOCD151I80V10C25A9000000/?type=my#QAAUAgAAM

Afterword

As Japan’s universities continue to internationalize, the number of institutions offering full degree programs in English is expected to grow steadily. This trend reflects a broader shift toward global engagement in higher education. However, as discussed above, implementing English-medium instruction and fostering a truly international academic environment are complex undertakings that require more than policy declarations—they demand institutional readiness, pedagogical reform, and cultural openness.

For prospective international students, it is essential to evaluate whether a university is genuinely prepared to support English-speaking learners. This includes assessing the quality of English-taught programs, the availability of trained faculty, and the inclusivity of campus life. Superficial branding alone is not enough.

This platform is committed to providing accurate, practical, and up-to-date information to help students make informed decisions. Our goal is to support those seeking a truly global education experience in Japan—one that goes beyond language and embraces diversity, academic rigor, and meaningful cross-cultural exchange. We will continue to monitor developments and share insights that empower students to choose institutions aligned with their aspirations and values.